Hollywood and the Brain Development Revolution: New Book Tells the Story Behind ‘I Am Your Child’

The imagery was striking, and something few people had ever seen. On one side was the grainy black-and-white image of a child’s brain that was developing normally. Beside it was another brain, but even at the same age was very different. It was smaller and misshapen. In the course of this child’s early development, something had gone very wrong.

Images like these entered the public consciousness soon after a 1997 messaging campaign that went viral before social media existed. By the end of that spring, common knowledge built across decades of research on brain development had been reduced to a simple message: a child’s first three years are everything.

Parents were left with one overriding question: How can we avoid destroying our children’s future?

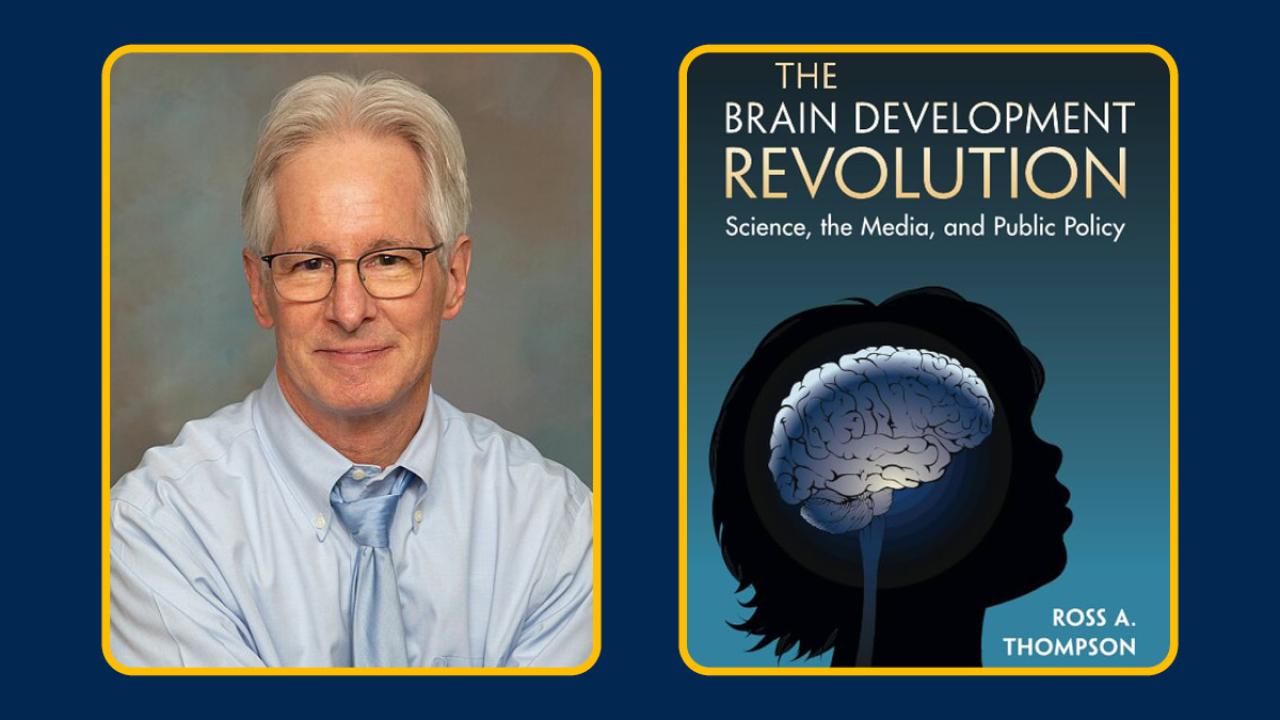

“The neuroscience research was astonishingly new in those days,” said Ross Thompson, Distinguished Professor Emeritus of Psychology in the College of Letters and Science at UC Davis. “It was enough to get attention for the idea of brain development, but there wasn’t enough neuroscience research at the time to talk about what parents and policymakers should do.”

Thompson’s new book, The Brain Development Revolution: Science, the Media, and Public Policy (Cambridge), is a unique work of scholarship. It tells the story of the 1997 “I Am Your Child” campaign with an incisive analysis spanning how the campaign captured everyone’s attention, the backlash from scientists and the continuing reverberations today.

Hollywood gets behind the first three years

In the mid-1990s, Rob Reiner had achieved the status of kingmaker — and moneymaker — in Hollywood. Throughout the ’80s and ’90s, he produced and directed some of the biggest box office hits, including Stand by Me, When Harry Met Sally and A Few Good Men.

It was at that time when Reiner read the 1994 Carnegie Corporation report “Starting Points: Meeting the Needs of Our Youngest Children.” The report highlighted the critical importance of a child’s first three years and how those early experiences affected lifelong development. It also documented the “quiet crisis” of children facing neglect and abuse at home.

The “Starting Points” report resonated with Reiner, but a very specific part of it rose to the surface: the three pages that discussed early brain development.

One of the first actions Reiner took was to call Tipper Gore, who at the time had high visibility nationally both for her work in mental health and as wife of then-Vice President Al Gore. When she suggested Reiner get in touch with the team who wrote the report, he convened a briefing.

What resulted was the campaign “I Am Your Child,” and in the spring of 1997 it took mass media by storm. Katie Couric talked about early brain development on Today. Good Morning America showed a five-part series on the subject. Stories appeared in Time, Newsweek and countless publications big and small. The “I Am Your Child” campaign even shared its ideas directly through videocassettes, booklets and CD-ROMs.

ABC even aired a one-hour prime-time special written and directed by Reiner. The special, also called I Am Your Child, starred leading figures from Hollywood including Tom Hanks, Michael J. Fox and Mel Brooks. Special guests included President Bill Clinton and first lady Hillary Clinton, who would also convene a conference on early brain development at the White House. Colin Powell, who had been President George H.W. Bush’s chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and was considering running against Clinton in the next election, was filmed reading Goodnight Moon to his grandson.

“In the space of two weeks, you would have had to have been living in a cave to not get the message that a child’s experience in those early years lasts forever,” said Thompson.

Scientists push back

The campaign was a smashing success. However, the simple story that a child’s first three years are the most important developmentally wasn’t exactly what the science said, according to Thompson. In fact, said Thompson, all of the campaign’s recommendations, such as regularly reading and talking to children, didn’t come from neuroscience research but from behavioral research.

In response to the campaign, John Bruer, a philosopher and expert in the application of neuroscience to education and policy, wrote the book The Myth of the First Three Years. In that book, Bruer detailed how “I Am Your Child” misrepresented neuroscience research. The book also made a case that the campaign vastly overstated the practical advice neuroscience could offer for everyday parenting.

Another general criticism, said Thompson, was that the campaign would drive all attention — and resources — to supporting children’s first few years when research had long shown that it wasn’t only those years that make a difference.

Thompson said that a particular flaw of the campaign was that it presented a child’s brain as having specific requirements that had to be met or brain development wouldn’t fully happen. As a behavioral psychologist who spent his career studying child development, Thompson said that’s not quite how it works.

“Parents were drawn to this mechanistic story that conveys a clear message that children need early stimulation during specific critical periods or these opportunities are lost,” said Thompson. “Behavioral research, which is what can provide some of the answers that neuroscience can’t, does not give you those kinds of recipes.”

A key missed opportunity of the campaign was that it completely lost focus on how poverty and hardship affect brain development. By the mid-1990s, said Thompson, scientists had already known for 20 years the devastating effects of experiencing poverty.

“Despite the amount of behavioral and neuroscience research showing the harms to early development from poverty, the campaign actually said vanishing little about the importance of addressing early poverty to promote healthy development,” said Thompson.

A flawed campaign does good

In spite of its flaws, the “I Am Your Child” campaign did have significant impacts on programs and policies for young children. Until then, said Thompson, there had been no action in terms of policies or programs that could make a difference. It also refocused how scientists communicated about child development research.

In 2000, the National Academy of Sciences produced a new report, “From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development.” This report integrated new research from neuroscience with research from behavioral science that provided clear guidance for the home, for neighborhoods and for large-scale public policy to support child development. Thompson, then at the University of Nebraska, was on the report’s committee.

“I Am Your Child” also led to new support for public programs focused on children’s earliest years. Among them are First 5 California, a state-funded initiative that was established through a voter-approved proposition in 1998.

The campaign also gave new visibility to organizations like Zero to Three, a national nonprofit that was founded in 1977 at the National Center for Clinical Infant Programs. Zero to Three translates the science of early childhood into programs and policies that support babies, toddlers and their families.

Thompson has been on the board of Zero to Three since 2005, even serving as board president. On Sept. 20, the organization awarded Thompson its Lifetime Achievement Award, both for his work on their behalf but also for his applications of research on early parent-child attachments and children’s psychological development.

Thompson’s outreach through Zero to Three and other organizations throughout his career has proven to be an effective way to get science into places where it can make a real difference for children.

“Scientists have a responsibility and an obligation to know the science best,” he said. “I can’t think of anyone in a better position than scientists to get the science out there.”