Q&A: Ron Mangun and the Future of Mind and Brain Science

Founding director resumes leadership of the UC Davis Center for Mind and Brain

When George “Ron” Mangun led a campuswide effort to launch the UC Davis Center for Mind and Brain in 2002, he declared, “This is the most exciting time in mind and brain research in human history.”

Now back for a second stint as the center’s director, Mangun sees more potential for mind and brain breakthroughs than ever before.

“What we are capable of doing now, and what we are learning with new methods and approaches, excites me even more,” he said. “I believe the next decade is going to see some of the most important discoveries about how the brain gives rise to the mind.”

Mangun succeeds Steven Luck, distinguished professor of psychology, who replaced Mangun in 2009. During the past 10 years, Mangun, a distinguished professor of psychology and neurology, has served in leadership roles in the College of Letters and Science — as dean of social sciences (2008–15) and interim chair of the Department of Psychology (2016–17).

John Jonides, a cognitive neuroscientist and psychologist at the University of Michigan, said the UC Davis Center for Mind and Brain is on the rise.

"Under the leadership of Professor Mangun to begin with, the center emerged as a vital international force in the study of mind and brain. That momentum grew under the direction of Professor Luck, and it is bound to grow yet stronger under the return of Professor Mangun as the intellectual leader of the center.

"The breadth and depth of research that is conducted by center members and the breadth and depth of the educational experience for students at all levels is impressive and bound to become yet more impressive under Professor Mangun’s leadership." — John Jonides, Edward E. Smith Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience, University of Michigan

In an interview, Mangun talked about the evolution and vast promise of mind and brain science and the role the Center for Mind and Brain (CMB) plays in the field.

What drew you back to directing the center again?

The CMB is a special place, where ideas flourish and the next generation of mind and brain scientists are developing new ways to understand the nature of human thought. The work we do at the CMB also has direct and meaningful impact not only on human knowledge, but on the lives of individuals who are challenged by disabilities and disorders of mind and brain, including developmental disorders, neuropsychiatric disorders and brain damage.

Having the chance to once again support these varied activities is a rare opportunity, and when asked to do it, I simply could not say no. Stepping back in as director is an honor. It’s not a job. It’s a mission.

What are your priorities as director?

At every five-year juncture since its founding in 2002, the CMB has reinvented itself to reach for the cutting edge of mind and brain science.

The past 10 years, under the remarkable leadership of Professor Steve Luck, the center nearly doubled in size to 21 resident faculty members and their laboratories, and underwent a tremendous expansion in translational research. That is, research aimed at taking the basic science of mind and brain research and applying it to disabilities and disorders that affect humans from birth through the end of life. Luck’s vision of the CMB as a hub that connects mind and brain research on campus was transformative — not only for the CMB but also for the campus. I want to continue that spirit, and help the CMB reach out determinedly in yet other directions.

What are the new directions in mind and brain research?

There is tremendous international excitement in mind and brain research for the promise of the general areas of computational sciences (including mathematics, statistics and computer science) and engineering and physical sciences, and the CMB is perfectly positioned to catalyze cross-disciplinary research in these directions. For example, engineers at UC Davis are working to help people with spinal cord injuries, figuring out ways the brain can control supportive devices, and how implanted devices might help the damage nervous system to function. There are parallels for cognitive disabilities and disorders.

We at the CMB understand the cognitive brain, the systems of the brain that do all the thinking. We also have significant interest in disorders of cognition. So, we are asking how we can begin to address those problems by drawing mind and brain science together more intimately with computational, engineering and physical sciences.

I will focus significant effort on strengthening the already strong ties we have across campus in these areas. There are real opportunities here for developing new research and training programs. And as I indicated, these directions will also support the continued success of our translation efforts, which have such high impact on individuals and society.

How do you develop the next generation of mind and brain scientists?

I believe the path is similar to how we created what we now call cognitive neuroscience. To build that, 30 years ago we began to bring together cognitive psychologists and neuroscientists to create a new discipline, training students accordingly. The CMB has had a major role in this internationally by hosting the Cognitive Neuroscience Society, producing the leading textbook in the new field, and running popular training programs.

Now is the time for the next step. It’s not enough to collaborate with those in the computational, engineering and physical sciences; the real gold is when our students co-train with each other.

So, when they are senior scientists, they are not simply engineers or cognitive neuroscientists looking to collaborate with each other across disciplines, they will instead be a new discipline of savvy scholars who both understand mind and brain science and the methods, tools and ideas of the computational, engineering and physical sciences.

We have already begun this effort. Since 2010, I’ve directed the annual Kavli Summer Institute in Cognitive Neuroscience, which is supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health and a generous gift to UC Davis from the Kavli Foundation. The institute brings together doctoral students, postdoctoral fellows and faculty from around the world with expertise in cognitive neuroscience, computational science, computer science, engineering and the physical science for training in how the brain enables higher mental function. Our experiment is jump-starting this cross-disciplinary training of the next generation.

Another of my goals at the CMB is to enhance support for the training of UC Davis undergraduates. The CMB trains more than 100 undergraduate research interns every year. These students are among the best at UC Davis, or anywhere, and they are intimately involved in the mind and brain science we do.

But there are some challenges they face; they are in desperate need of scholarship support to enable them to spend more time in research training. I hope to greatly increase support from alumni and other partners to give these talented young UC Davis students the chance to explore mind and brain research in one of the leading international centers, the UC Davis Center for Mind and Brain.

What are the center’s research strengths?

Our focus is on the mind, meaning our thoughts, knowledge, intelligence and creativity. We know that the brain gives rise to the mind, but that is simply the launching point.

The CMB comprises expertise in several core areas, including:

- visual and auditory cognition (including music and the brain)

- development science

- language and understanding

- learning and memory, and

- decision making, including how these processes are affected in disabilities and disorders ranging from deafness and autism, to schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s Disease.

Let me give you an example of a fascinating project with immense societal implications.

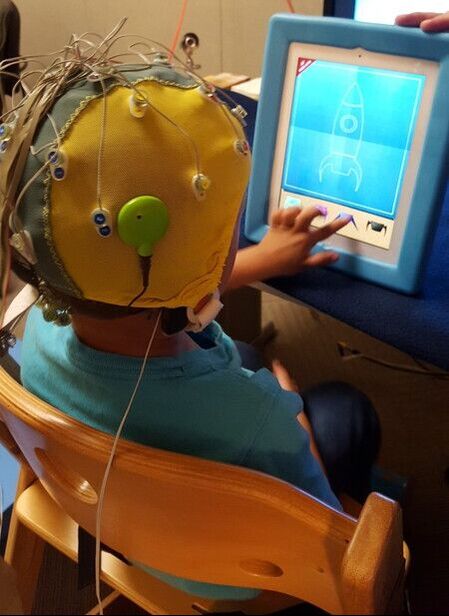

CMB faculty members Dave Corina (Linguistics) and Lee Miller (Neurobiology, Physiology and Behavior) are studying children who have been deaf from birth. Most of us take hearing for granted, but what would it be like to have never heard a single sound? And more fascinatingly, what would it be like to have hearing restored as an infant or child?

Cochlear implantation is a form of brain-machine-interface that is being performed on thousands of children annually, restoring hearing, but after receiving cochlear implants some kids learn to use the sounds while others don’t: Why is this, even when the cochlear implantation is otherwise successful?

They believe that in addition to lower level auditory constraints, there may be factors that involve the brain’s higher level cognitive functions. For example, they are asking how the brain’s attention networks may be differently organized in these children to enable them to attend or ignore the new auditory signals their brains are now receiving, and are using brain wave recordings in this research. This is truly innovative work.

How did a linguist and a neuroscientist from different departments and colleges come together to build that research program?

That is one key feature of the center. We have 21 core faculty members, which leads to interdisciplinary research. That those faculty members come from several departments and colleges is a unique strength.

For example:

- My appointments are in the Department of Psychology in the College of Letters and Science, and in Department of Neurology in the School of Medicine.

- Associate Director Amanda Guyer is a professor of Human Ecology in the College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences.

- As mentioned our technical director, Lee Miller, is a professor in the Department of Neurobiology, Physiology and Behavior in the College of Biological Sciences.

- Physician John Olichney is a practicing neurologist at the medical center, and in addition to his research lab group at the CMB he is a key faculty member in the UC Davis Alzheimer’s Disease Center.

This facet of the CMB streamlines the bringing together of different methods, approaches and skills for mind and brain research, and helps the center to be an important hub from such research and training on campus.

What advances in cognitive neuroscience the past 10 years have surprised you?

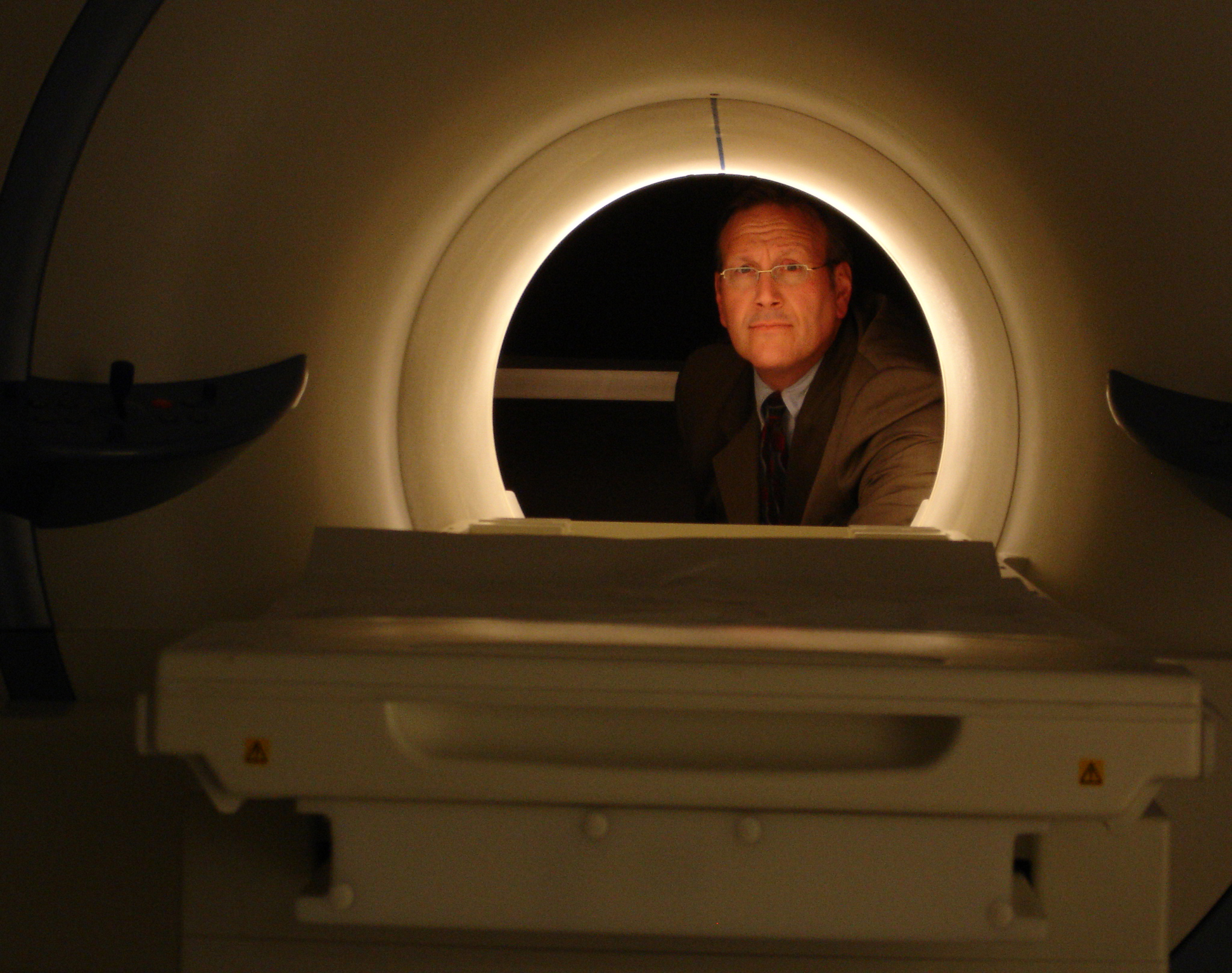

There are so many! Our ability to manipulate the human brain is one.

In the beginning of human mind and brain research we were just trying to measure the brain, look at it with brain scanning or recordings of electrical activity, and whatever else we could do to study human brains.

Now it’s possible to go in and manipulate the brain — that is, change its function by stimulating brain cells using noninvasive (electromagnetic) and invasive (surgical) methods (the latter only in patients, of course).

These approaches can be used to study the functions of the mind and brain, but also have tremendous promise for treating many disorders.

By stimulating the brain from the outside using electrical or magnetic methods the hope is that we can normalize brain activity, then we might be able to help the healing and reorganization of the damaged brain, but also augment the healthy brain. This is a big thing, and it is the future, but it is here today.

What are CMB researchers on the brink of discovering?

Science, most of the time, is a slow slog, and we’re trying to understand the most complicated thing in our known universe: the human mind and brain. So, that brink might be measured in decades. But there are several lines of research at the CMB that I see as poised for transformative leaps forward in human knowledge.

One example is the work of our visual cognition group. A major focus of our efforts is understanding the complex nature of momentary human experience. A central theme is the investigation of how the brain focuses attention on the world around us, as well as inwardly on our own thoughts. These cognitive neural processes give rise to our individual momentary reality, and studying them is puts us on a path toward understanding the nature of conscious awareness, the very essence of the human experience.

Nobel Prizes will be awarded for the discoveries made along this search for the Holy Grail of the mind. Although I cannot promise one will come to UC Davis, I would not be surprised!

What is an example of this Nobel Prize-seeking research?

Well, I have painted myself into a corner, so I have to come out swinging, and in fact there are several promising lines of work. But the one that pops to mind first is the recent work published by John Henderson and his postdoc Taylor Hayes in the journal Nature Human Behavior.

They revealed how the meanings of objects in natural visual scenes guide our attention to the world. This was a fundamental advance because earlier work focused on low level aspects of scenes such as visual salience (stimulus brightness, motion and so on) to describe how attention is attracted. Their focus on meaning, which involves the high level information that we learn throughout our lifetimes, provides a new way to view visual cognition.

As we struggle to understand disorders of attention, or to build robots with sophisticated abilities to perceive and navigate in the world (think auto-driving cars, like Teslas, or autonomous robots on Mars), this discovery of meaning maps in the mind promises to revolutionize our thinking.

You are very enthusiastic about the questions and answers coming out of work in mind and brain science — what is so exciting about it?

You know, there is nothing I can think of that is more mysterious than the workings of the mind and brain. Personally, I enjoy all kinds of scientific exploration and scholarship, but when it came to how I wanted to spend my life, the mind and brain easily won out.

The human brain is exceptionally complicated — close to 100 billion brain cells, each connecting to thousands of other neurons in exquisite, highly specialized circuits, networks and systems — it is the most magnificent structure in the natural world, and nothing rivals its complexity.

So, we are just scratching the surface of understanding the mind and brain, and we won’t fully know how it works for some time, certainly not in my career. Investigating the mind and brain is the kind of scientific mission that represents one of the great challenges facing humanity, and it takes time, and money. It also requires interdisciplinary cooperation, and the training of new generations of mind and brain scientists. They, like astronauts leading us to the stars, will follow the trail we are laying out today to discover the very nature of what it means to be human. What can be more exciting than that!

— Interview by Kathleen Holder, content strategist in the UC Davis College of Letters and Science

Video:

In this 2015 overview, former director Steve Luck describes the center's interdisciplinary approach to studying the human mind and how it arises from the interconnected neurons of the brain.